Happy Monday, folks,

Some inspiration for a creative week.

What does it mean to ‘innovate’? Many look for the decisive mark of the singular genius or the cutting-edge company. Perhaps the best-known recent example is Elon Musk and Tesla. Not too long ago it was Steve Jobs and Apple. However, you might be familiar with Mariana Mazzucato’s retelling of Jobs’ (iPhone) story. In her reconstruction, she shows how all the constituent technologies of the iPhone – the HTTP protocol, GPS, LCD displays – were technologies developed with state support and often within public bodies. All fundamental innovation had happened previous to the iPhone.

While her analysis dispels the “I built that” theory of innovation, that still leaves (Jobs’ and Musks’) actual creativity unexplored, which is the art of assembling new technologies, ideas and (business) practices into a product or service that changes our world in a meaningful way.

We’ll talk about this creative work in today’s edition in my ongoing series on renewable energy markets. Two main questions drive the series: how are new markets made and what good can products and services do? Today, I’ll dwell mostly on that first question.

As a case study, I’ll take a look at Sunrun, the US solar-as-a-service company. I’ll base my examination on a conversation that co-founder (and current CEO) Lynn Jurich had with energy journalist David Roberts for his Substack newsletter Volts, which I recommend to you all, if you’re not already subscribed.

Here’s what to expect: first, a quick overview of how Sunrun can be considered innovative. Then, an analysis of what it actually entails to make Sunrun – and its business model – successful.

My analysis is directly inspired by this week’s reading:

Beveridge, Ross, and Simon Guy. 2005. "The rise of the eco-preneur and the messy world of environmental innovation". Local Environment. 10 (6): 665-676.

Strap in, for the ride is now in motion.

Phase 1: Solar as a service

When Sunrun started out in 2007, they wanted to increase adoption of rooftop PV by reducing the upfront costs and the hassle of the paperwork. It did so by paying for the installation of the solar panels itself, becoming the energy provider for the home, offering lower energy bills than the current contract, and recouping the costs by selling the solar harvest. Sunrun was (among?) the first to offer this ‘Lease’ + ‘Power Purchase Agreement’ combo in consumer PV.

Phase II: Household energy management as grid service

Now batteries have entered the picture. Their steeply falling costs means it is now possible to perform the same trick as with rooftop PV. With batteries, Sunrun can recoup the costs with grid balancing and peak shaving. Batteries can respond near-instantly and importantly, they are installed locally, which means that can also help balance the distribution grid. In theory then, home (and EV) batteries build up to a “virtual power plant”, a plant that should be able to (ultimately) replace fossil fuelled “peaker plants” in the growing market for ‘flexible energy capacity’.

Street smarts: werk!

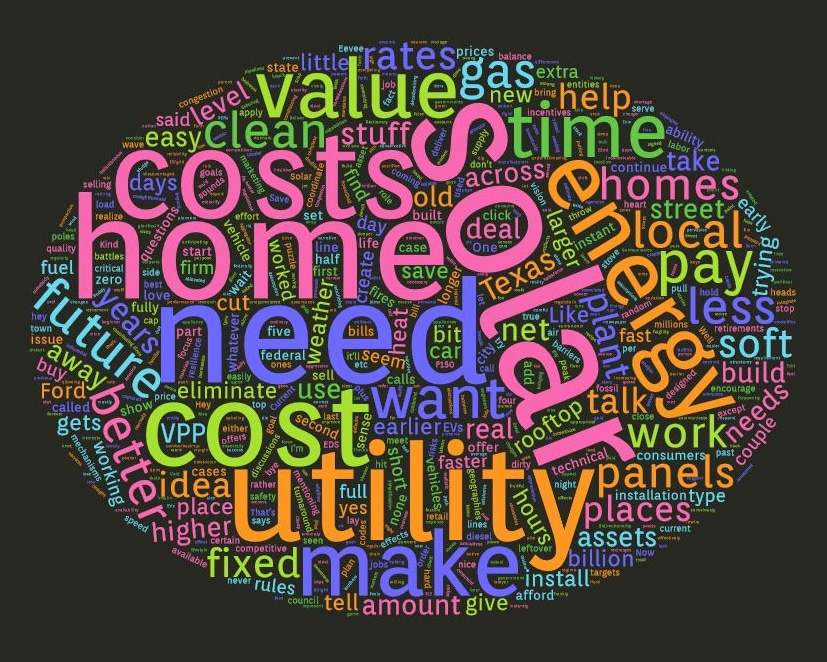

Right from the get-go, Jurich tells Roberts that she wants to make clear that she doesn’t just know the theory of sustainable energy business models, but that she has the “street smarts” to put them in to practice. That’s a great way of describing the actual work of collecting and arranging all the different – social, legal, technical – ingredients of the business model.

Why would that require ‘street smarts’? There are obstacles in the way, like red tape and opposition or at least disinclination from utilities. It can also be difficult to reach homeowners, who might not know about this possibility, might be sceptical about its long-term value, fear drawbacks (like for comfort), and don’t upgrade their home very often to begin with, which means there’s a small window to catch them.

Alright, so what work are we talking about then?

Storytelling

Streets smarts is all about schmoozing. It’s about knowing how to sell a story. In this case: a story “about sustainability and possible future relationships between the environment and business” (674).

“We’re great at creating value for homeowners and utilities.”

Let’s take the examples of Sunrun’s main interlocutors: the electric utilities. To Roberts, they are the main obstacle for distributed energy generation. Why? Because most for-profit utilities make their money ‘selling’ the construction of new infrastructure to the state (much more than selling energy to their customers). So their interests are diametrically opposed to people taking infrastructure into their own hands (or homes, rather).

In response, Jurich tells a story of a world in which distributed infrastructure is no longer opposed to grid-scale infrastructure. In this world, there is enough to go around for everyone.

We need more abundant thinking: we can have a better experience for customers, and a more competitive distributed energy resources market. There’s no shortage of value to go around.

In other words, she’s saying, getting hung up on investment-based business model is a distraction. Instead, utilities could remove administrative barriers which wouldn’t cost them anything, but will save parties like Sunrun huge amount of “soft costs” and allow them to build out a market that will benefit everyone. We will need so much electricity in the future, everybody can win. Let’s not fight (over how infrastructural investments are going to be paid for).

In other words, she is inviting other actors into her vision.

Dissociation/association

Established ways of working are successful because the different ingredients have been made to work with another. To make room for new ways of working one needs to loosen the establishment’s grip on these ingredients. In Beveridge & Guy’s words:

How does [Sunrun] ‘disentangle’ users of traditionally sourced electricity from the web of relationships they have with the suppliers, consultants and engineers supporting it and then reassemble them in a new arrangement around [its] innovation? (674)

Sunrun’s Power Purchasing Agreement – itself new at the time – was meant to lure customers away from familiar fossil-centric home upgrades that had lower upfront costs. Home solar needed to become attractive and reducing upfront costs and hassle was one way to do that.

But it has also lured in the utilities. One of its earliest partnerships with them was to offer the tax credits reserved for home PV in exchange for cash-financing the installations (so-called ‘tax equity investment’). It was a way of unlocking large streams of money, especially just after the 2008 financial crisis, but it was also a way to get the utilities on board, disentangling them from their usual mode of operation.

It’s not just about disentangling though, it’s also linking things up.

Take its recent partnership with Ford. The company has made Sunrun the preferred installer of home chargers for the all-electric version of its iconic pick-up, the F-150. Ford is betting on Americans’ undying love for this particular vehicle, and its place in popular culture is something Sunrun can capitalize on as well. Enrolling EVs in general into this business model makes financial, technological and social sense as well, since people want their cars to run on the sun (aaahh) and its battery can serve the house and the grid.

The messy process of innovation

Loosening and linking does not come without friction. According to Beveridge and Guy, innovation is therefore all about the messy

interplay of competing discourses of business and the environment, the flow of national and local technology politics, the trade-offs, compromises, deals and conflicting visions. (672)

But there’s another sense to this messiness: the fact that the ingredients of new business models do not yet ‘align’ (the way they do in the established ways of working) and that it’s Sunrun’s interest and job to make sure they do. For distributed electricity generation and virtual power plants to ‘stick’, the process of putting them in place needs to be streamlined for everyone involved.

This comes to a head in a concept that seemed to dominate the discussion: soft costs.

Electric vehicles are a huge unlock for decarbonization but the customer experience can be confusing. There’s the utility, the dealer, the electrician and the manufacturer and many times they don’t really talk to each other. That’s what we’re great at: we can be the energy adviser. And from a business model standpoint: when you buy an EV, we put more panels on the roof, and that small increment in power is the cheapest to build. When you’re already spending time at the house, get the permit, get installers there, the extra panels are the cheapest on the grid.

As you can see, Sunrun is trying to 1) reduce messiness for customers (aiming at that one-click-buy™ equivalent for home electrification), 2) create a more compelling narrative for adoption of Ford’s EVs, and 3) by actualizing connections in their service, reduce friction for themselves and strengthen their business case by increasing generation capacity.

So there you go, that’s the theory of innovation-by-assembly! To close, I’ll let Jurich have the final, illustrative word:

Roberts: So basically you offer a full home electrification service.

Jurich: Yeah, we have the trucks, the labour, the sales force, the ability to tell what your utility bills will look like before and after, how it links up with the electric panel, roof and car. We educate and provide the service. That’s why Ford wanted to partner with us: we can make buying EVs easier.”

Hope you have a good week. More sustainable entrepreneurship to follow. Did you see anything amiss in this edition? Let me know!

Take care,

Marten

PS Not done reading yet?

If you missed the two earlier issues in this series:

Making markets for sustainable energy. Or how to produce customers for solar lamps in West Africa.

Recognition should be at the heart of the energy transition. Plus: build your own solar water heater!

Want to read more about innovation in clean energy?

Share this post