Full interview with Christine Milchram on energy justice in smart grids

I talked with Christine Milchram (LinkedIn, Twitter), who’s currently wrapping up her PhD thesis at TU Delft, about what the concept of energy justice means for how we can design “smart grids” – the ensemble of technologies and price structures that tackle the challenges of decentralization of energy production and the variability of renewable energy generation. She has done great work in breaking down the notion of justice in actionable categories. Read on for the full interview or check out a shorter version of the interview first!

In order of appearance, we will talk about the rise of the idea of energy justice, about what smart grids are, what smart grids might mean for citizen involvement in energy, and how about to break down energy justice in different aspects and different domains of application.

The interview has been slightly edited for clarity.

Energy justice

Marten

Let's start out with your research and what you wanted to accomplish with it. What did you do?

Christine

Yes, well, from a technological perspective, my research is focused on Smart Grids and the societal consequences of the bigger societal impact, ethical impact even, of smart grids. And in the course of my work, I discovered that the concept of energy justice, or concept of justice in the energy transition, became more and more important. There was a growing body of academic literature that specifically uses this energy justice concept more and more in a theoretical way, but there was also a growing practical discourse on climate change, on sustainability transitions, that achieving a fair transition, or a just transition, or transition that is inclusive for all became more and more important in the last years. The last COP before Madrid, the one in Katowice, I believe, was under the motto of a just transition. The Green Deal announced by the new president of the European Commission is a lot under the motto of justice or fairness as well. And also in the Netherlands, when we debated the Klimaatakkoord [Climate Accord] at the beginning of 2019 or in the Klimaattafels [Climate negotiation rounds with corporate sector and interest groups] that are happening now, there is a lot of talk about citizen participation, that we have to make this transition inclusive for all, to somehow achieve an energy transition for all and by all.

I think this development is a recognition that the energy transition per se is as much deployment of different technologies, as much at it is a redistribution of power and wealth. It's fundamentally social. And, and I think a good example for that is the role of energy communities that we see now, or the energy cooperatives, that we see now in the EU Clean Energy for All Europeans package, where they get a much bigger role and they are recognized much more than I would say in the in the past.

So I saw during my research the increasing importance of the concept of justice, but it was at the same time all very vague. I didn't observe really concrete policy guidelines or technology developer guidelines. If I say, what should I, as a policy maker, do to implement justice? What does “just participation” mean? How should costs and benefits really be distributed? It’s not that clear. And since my work was about smart grids, I set out to do a study where I thought, okay, I would like to make clearer. I would like to, at the end, to be able to give detailed recommendations, especially for technology developers. If you want to design for justice in smart grids, that's what you can do. [If after reading this you’d like to know more about these recommendations, please feel free to contact her – MB.]

About Smart Grids

Marten

Yes, smart grids. Maybe you want to give us a little bit of background of what were the things that you looked at or what the specific challenges are with ‘smart’, in terms of energy justice?

Christine

I’ll start out by saying something basically about how I conceptualize or how I view smart grids in that research. As we see the energy transition playing out, from the perspective of citizens, that's really the perspective that I have, as we're adding much more renewables. We're seeing this trend of decentralization in energy supply. Supply is smaller, more dispersed throughout the country, ordinary citizens can own and generate their own energy they can become prosumers. We can participate in energy communities and own for example, a wind park or a solar park together with another group of people. So, there's this trend of additional renewable energy that is very decentral, which at the same time is a trend to open the electricity generation to more citizen involvement.

Smart grids are some extent a continuation of that trend. From a technological perspective, as you add more renewables to the grids that are dependent on the weather, such as wind and solar, you can predict and control to a much lesser extent how much supply you get. And the electricity grid of course always needs to be in balance between supply and demand. And the electricity network as it is now also always needs to be able to take up all the supply peaks that you might have from a wind park or a solar park, but also single solar panels on rooftops. And, and what we do now basically, to solve these additional volatilities in supply from renewables, we either tell the solar panel to shut off at a certain voltage, or curtail the wind park, or we need to expand the grid. And the first option, the curtailment is a waste. Second option to expand the grid is extremely expensive. It’s also complicated because our infrastructure, especially in a densely populated country such as the Netherlands, is already quite dense. It's really hard to find new locations for additional cables.

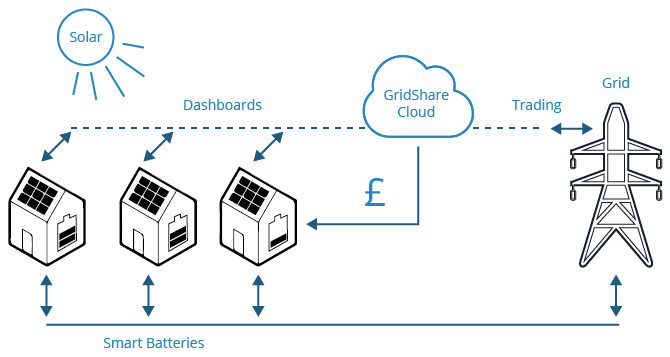

So, there's this nice solution, broadly called “smart grid”, which is essentially a catch-all term for digitalization in the electricity network. It gives us more flexibility. When you have a supply peak from renewable generation is allows to adjust our demand to the supply peaks. For example, when I when I have the house and I own solar panels, right now what happens is whenever they produce, you feed all of the electricity back into the grid, no matter whether the grid can take that at that moment or how the network load is. And once the network loads gets too strong, the solar panels will shut down. What you could do though is add storage to the solar panels, a home battery for example, so that when the solar panels generate and when you have a high peak rather than putting it back on the grid, the battery stores the electricity. Now, the steering of the battery requires additional IT systems that are not yet applied on a large scale. So that for example, your battery is not already full that 11 o'clock in the morning, but that your battery can capture the big solar peak at 1pm. And so that's one example of these smart grid systems.

“Virtual power plant”: one of the ‘smart grid’ solutions, involving battery storage.

Citizen involvement in energy

Marten

And you said it would help citizens become more involved, at least that’s the idea, that it will continue that trend of involvement?

Christine

Yes, exactly. So, I think another example highlights that's even better. When you want to adjust your electricity demand to the time when you have supply from your solar panels, you can incentivize this with variable tariffs, so that citizens can profit from cheaper prices when the sun shines for example. Or you can also optimize this within a neighbourhood. For example, you can say, my neighbour has solar panels and he's producing energy when I need it, and then you can actually buy it from them, which is something that is not allowed or not available now. So what we're talking about here is really quite…

Marten

cutting edge!

Christine

…emerging technologies yes, and technologies that are really applied right now on a small-scale pilot project size, but really become hopefully more adopted in the future, because if we want to add more renewables on the grid, we need the flexibility. And it means continuing this process of citizen involvement, because it continues to make the electricity system more transparent for citizens and it continues to increase the options for actions. I can, I can not only generate, but I can also store electricity, I can share it with my neighbours, and through an app or an in-home display for example, I can see immediately, in real time, how the energy flows in my house are developing, I can see if I switch on switch the kettle, and there's a spike in my electricity consumption.

Marten

And why’s that good?

Christine

This is good on the one hand, because the promise is, through these technologies we can add more renewables, and the other reason this is often seen as good is because this process of citizen involvement or citizen empowerment is seen as making the system fairer.

Marten

These are two things, the environment and fairness, or are they related?

Christine

I think they're often interrelated with each other. I think that the dominant discourse or the promise you also hear around smart grids, is that if citizens are more empowered, if they're more involved in the electricity system, if the electricity system is less of a black box for them, then they're less dependent on the big energy suppliers, they can do more on their own, it will be more fair for more citizens than it is now.

But I'm also very critical of this because I think it is to some extent, a promise or a vision for the future. And there are some challenging details that we haven't looked at. It’s questionable, if this vision can really be fulfilled. So that's partially what I wanted to do in my research as well. If there is this promise that smart grids contribute to a more just electricity system, what does that actually mean? And if that depends on the designer of the technology, what can the technology developer or designer do to design for justice?

Marten

What would be some obstacles to realizing this vision of the fair smart grid?

Christine

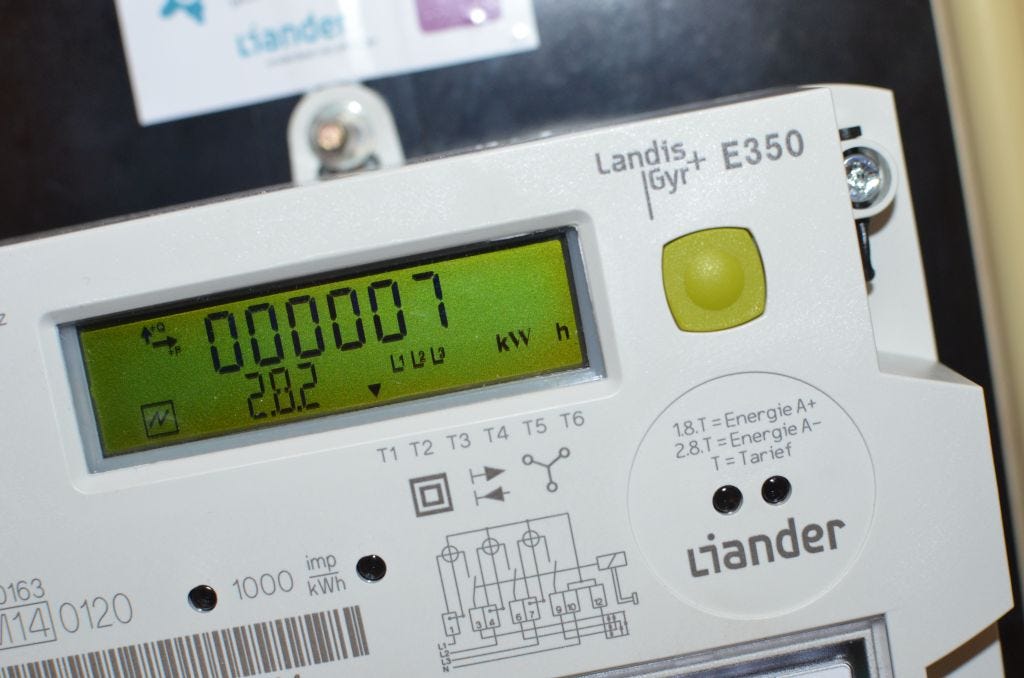

One example would be that these technologies that we're talking about, for example, storage, is quite expensive, and it needs space in your house. So, often, these technologies are much more accessible for the parts of the population that are highly educated and that have a high income. And the other thing is for example if you imagine you have your nice in-home display and it shows you all the energy flows: the degree of transparency that you can get in the electrical system is really dependent on what that display looks like. Because electricity, of course, is normally invisible. You can only make it visible by measurement. And yeah, I think that will be a more technical challenge: whether you can actually do something as an ordinary citizen, depends on how the developer has developed the app.

Smart meter display (photo by Luuk Oosterbaan)

Marten

Are these are also some challenges that you've actually looked at in your research.

Christine

Yes, I have. In the context of this question, energy justice is important. But it is a relatively vague concept. And it's not as clear what you what you should do as a technology developer. And that was my starting question. The beginning of this research project that I said, okay, and what does, how can I break down energy justice into an actionable concept for a technology developer? And when we talk about justice in general, we often talk about the distribution of costs and benefits and harm more widely. Who gets what, and who pays what?

Breaking down energy justice in smart grids

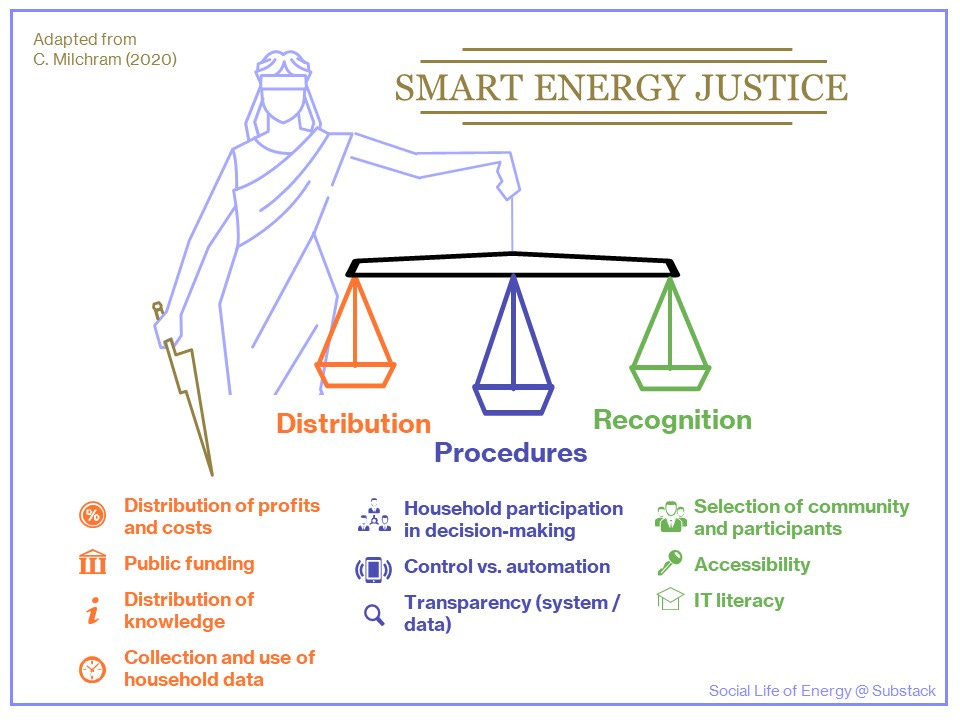

Christine’s breakdown of topics for energy justice in smart grids.

Marten

Okay, so “distribution”.

Christine

Yes, the distributive aspect. When we talk about justice, we also often talk about participation or inclusion in participation processes. And so that's the more procedural aspect. And the energy justice concept has a third dimension, which I call justice as recognition, which basically aims at making sure that benefits from the development are accessible to everybody. That different opinions in the decision-making process, for example, are recognized and respected in an equitable way.

Marten

Okay.

Christine

And these are still quite theoretical and vague, I would say, for a technology developer. So, I then broke these down into five concepts or five topics where I thought: if I'm a designer of smart grids, and I want to design for justice, this is what I should do. The first important one, which also is a lot about distributive justice, is how do I distribute benefits and harms from my system. And that is quite literally, profits and costs. Let’s say we are building this new system, which is a collaboration between a distribution system operator (DSO) and some citizens and some apps developers and maybe an aggregator. And then the question is who is actually gaining the profits and who is paying for these technologies.

Distributive justice

Marten

This relates to the example of the storage solution as something that is only available to certain people?

Christine

Yes, that could be a good example here. If the technologies are really accessible only to higher income and higher educated people and gain the profits. What about lower income people? What about what about social housing communities? How can we how can we design the technology so that they are also accessible to those groups of people?

In my research for example, I had a case where they had a smart grid with a social housing community. And what they did is they had solar panels through a rental system. They rented solar panels from the municipal energy supplier. And then in addition to that, they installed a community battery. So it's a battery that is not a home battery individually in all of the houses, they sit in a large container at the street corner, and the entire community has access to it. The battery was funded by the distribution system operator and because you need less additional technology than comparable home batteries, it is in some aspects, the cheaper option, and it means that the individual households, the social housing tenants didn't have to invest in their own batteries, but they could still get access to the ones that are standing at the corner. I think that was a good and rare example of how these technologies can be made accessible to a social housing community.

Neighbourhood battery near Amsterdam (Photo by Liander).

Marten

Because the power that they would get from the battery is cheaper than what they would have otherwise gotten from the grid?

Christine

Indeed that would be the intention. With the current Dutch regulatory structure of how we pay for electricity, that’s not yet possible. But the concrete kind of cost-saving that I had in mind, which is already happening now, is when you have these 30 households and everybody has to invest in the home battery, and they also need all an inverter between the solar panels and their home’s electricity grid and then the battery again. And if you have that only one time on the street corner, which is attached to the community battery, you only need to invest in this once. So these are kind of kind of cost advantages that you can have already now. And in the future, indeed, once the regulation for how we incentivize renewable generation through net metering changes, the electricity from the battery should also be cheaper for households than the electricity that they take from the network.

Procedural justice

Marten

You also mentioned empowerment and transparency. Did this project also do anything in that dimension? Did it allow a greater scope for action? Or it is only question about costs and benefits?

Christine

No, I think it did it, if we talk about transparency and empowerment, it's probably worth talking about the next two kind of topics that I broke energy justice down into. One of them is the IT systems and how you design IT system such that, for example, the amount of control users have. I can control their own action, but for the optimization of the network of the smart grid, you do need a certain kind of automation. So, how you strike that balance between user control and automation is important. You just mentioned transparency as well. So, how do algorithms optimize this local smart grid system? For example, the degree to which this is transparent to the users is also an important aspect of justice that I would suggest needs to be taken into account when you want to design for justice.

Transparency is also really important when you talk about the next sub-topic of energy justice that I defined, which is data governance or data management. It's very important that for the system is transparent and it is understandable how their personal data is used and by whom. And like we said before, electricity is invisible and you can only see what you can measure. Smart grid systems really rely on sharing and measurements of detailed, real-real time energy data. And that is, if I have solar panels, what electricity my solar panels are generating. That concerns how much is going into my storage but, most importantly, how much I'm consuming at a particular 15 minutes time span in a day. With just this data you can interpret actually quite in detail what is going on or what people are doing in the household. At the end we're not using electricity for the sake of using electricity but we're using it for cooking, or maybe even for heating, or using it for lighting, or using it for entertainment. And it has privacy implications if you can look at my personal energy consumption, and tell if I'm watching TV, or whether I have a very inefficient fridge.

And so in the system, if we talk about transparency, I would find it really important to define it as such that it is very clear to the user what is happening to that data. This transparency and privacy aspect of justice is something that is discussed a lot already with other digital systems, or with apps. For example, when we scroll through all the terms and conditions, and we just click on “I accept” because it's really fine print, we don't really read it and we don't really understand it. In smart grids as well then, it’s important that these systems are designed so that doesn't happen. That in an app before I click, I agree, and somebody has really put some effort in to making sure that I can give my consent to the data used in an informed way.

Marten

Have you seen any examples of that being done well?

Christine

And, to be honest, not yet that much. I also found in my empirical research that this issue was often not seen as an aspect of fairness. I found this startling, because we're talking about this so much with respect to other digital solutions or apps. When we talk about Facebook, when we when we talk about digital platforms like Airbnb, we're talking about it all the time, but not here. I found two reasons for that. One is that smart grids are seen much more as an energy system than as a data-based system. So, this aspect of how much they rely on real-time sharing of data is not discussed. There's not that salience for many users yet.

I think the second reason was that the pilot projects that I looked at in my research, they are often a collaboration of research institutes, of distribution system operators and citizens, and they are very much presented and framed as research projects. And I found that many of the users especially said, ‘well, we don't think this is an aspect of fairness right now, because we're doing the research. And we want to contribute to that research’. But they were also quite clear that if the same app or the same in-home display would be supplied by a regular market party in the future, they would be way more critical. The framing of the project as research played a huge role here. So I would be tempted to say that the more widespread the systems become, the more users see it as data-based systems and the more it is not framed as research anymore, but just a regular service that is also in the market, the more important or salient these data issues will become.

Marten

So DSOs or energy companies should already be thinking about and designing for this right now basically.

Christine

Yeah. Because if not, it could be a barrier to the adoption of those systems in the future. Or at least slow them down.

Christine and I had to wrap it there, but as you can see in her diagram and the inforgraphic below, she has thought these aspects of justice in more domains that he ones we covered here. All in all, these domains of energy justice build up to a step by step guideline for designers. Are you a designer and you want to do right by your pilot participants and energy users? Get in touch!