Hello everyone!

As I announced last week, I’d like this newsletter to become a platform for conversations informed by social science about how to make sustainable energy transitions happen more quickly and fairly. I hope to bring research and practice a little closer together. As part of that effort, I’ll be interviewing both researchers and practitioners about their work.

None better to kick off this new cycle than Christine Milchram (LinkedIn, Twitter). She’s currently wrapping up her PhD thesis at TU Delft about what the concept of energy justice means for how we can design “smart grids”. She has done great work in breaking down the notion of justice in actionable categories.

Below you will find excerpts from the interview. If you like what you read, you can check out the full interview here!

If you are inspired by the interview, or you would like to follow-up with your experience or a question, you can comment below this post (just click on the title of this newsletter, if you’re reading this in your inbox). Christine and I will be monitoring the comments section over the next two days, ready for your input. Don’t feel shy!

Marten

Let's start out with your research and what you wanted to accomplish with it. What did you do?

Christine

Yes, well, from a technological perspective, my research is focused on Smart Grids and the societal consequences of the bigger societal impact, ethical impact even, of smart grids. And in the course of my work, I discovered that the concept of energy justice, or concept of justice in the energy transition, became more and more important. There is a lot of talk about citizen participation, that we have to make this transition inclusive for all, to somehow achieve an energy transition for all and by all.

I think this development is a recognition that the energy transition per se is as much deployment of different technologies, as much at it is a redistribution of power and wealth. It's fundamentally social.

So I saw during my research the increasing importance of the concept of justice, but it was at the same time all very vague. I didn't observe concrete policy guidelines or technology developer guidelines. If I say, what should I, as a policy maker, do to implement justice? What does “just participation” mean? How should costs and benefits really be distributed? It’s not that clear. And since my work was about smart grids, I set out to do a study where I thought, okay, I would like to make this clearer. I would like to, at the end, to be able to give detailed recommendations, especially for technology developers. If you want to design for justice in smart grids, here’s what you can do.

Smart Grids

Smart grids are, as she says, a “catch-all term for digitalization in the electricity network”. Through digital monitoring and we can make it possible to adapt to the amount of electrons passing through the grid’s cables, by changing how much we consume or store at any given moment. Doing so might allow us to keep solar panels and wind turbines freely producing electricity and delay or avoid expensive and complicated expansions of the grid.

Marten

You mentioned earlier smart grids would allow citizens to become more involved, at least that’s the idea?

Christine

Yes, exactly. When you want to adjust your electricity demand to the time when you have supply from your solar panels, you can incentivize this with variable tariffs, so that citizens can profit from cheaper prices when the sun shines for example. Or you can also optimize this within a neighbourhood. For example, you can say, my neighbour has solar panels and he's producing energy when I need it, and then you can actually buy it from them, which is something that is not allowed or not available now.

The idea here is that this process continues to make the electricity system more transparent for citizens and it continues to increase the options for actions. I can not only generate, but I can also store electricity, I can share it with my neighbours, and through an app or an in-home display for example, I can see immediately, in real time, how the energy flows in my house are developing, I can see if I switch on switch the kettle, and there's a spike in my electricity consumption.

But I'm also very critical of [the idea that if the energy system becomes more visible to citizens, it will give them more power] because I think it is to some extent, a promise or a vision for the future. And there are some challenging details that we haven't looked at. It’s questionable, if this vision can really be fulfilled. So that's partially what I wanted to do in my research as well. If there is this promise that smart grids contribute to a more just electricity system, what does that actually mean? And if that depends on the designer of the technology, what can the technology developer or designer do to design for justice?

Marten

What would be some obstacles to realizing this vision of the fair smart grid?

Christine

For example if you imagine you have your nice in-home display and it shows you all the energy flows: the degree of transparency that you can get in the electrical system is really dependent on what that display looks like. Because electricity, of course, is normally invisible. You can only make it visible by measurement. And yeah, I think that will be a more technical challenge: whether you can actually do something as an ordinary citizen, depends on how the developer has developed the app.

Transparency! (Photo by Luuk Oosterbaan)

Marten

Are these are also some challenges that you've actually looked at in your research.

Christine

Yes, I have. In the context of this question, energy justice is important. But it is a relatively vague concept. And it's not as clear what you what you should do as a technology developer. And that was my starting question: how can I break down energy justice into an actionable concept for a technology developer? And when we talk about justice in general, we often talk about the distribution of costs and benefits and harm more widely. Who gets what, and who pays what?

Breaking down energy justice in smart grids

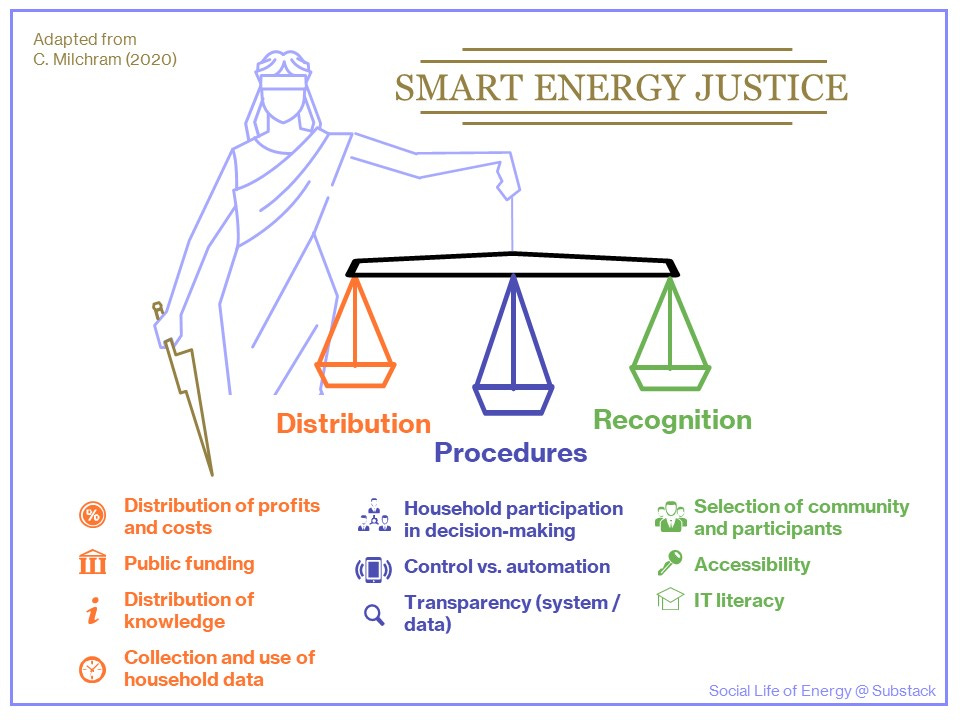

Christine’s breakdown of (smart) energy justice into values and their respective domains of application. (I had a little help from vecteezy.com in making this.) You can find a diagram with a different breakdown of the domains in the full interview, which you might also find useful.

Marten

Okay, so “distribution”.

Christine

Yes, the distributive aspect. When we talk about justice, we also often talk about participation or inclusion in participation processes. And so that's the more procedural aspect. And the energy justice concept has a third dimension, which I call justice as recognition, which basically aims at making sure that benefits from the development are accessible to everybody. That different opinions in the decision-making process, for example, are recognized and respected in an equitable way.

Marten

Okay.

Christine

And these are still quite theoretical and vague, I would say, for a technology developer. So, I then broke these down into five concepts or five topics where I thought: if I'm a designer of smart grids, and I want to design for justice, this is what I should do. The first important one, which also is a lot about distributive justice, is how do I distribute benefits and harms from my system. And that is quite literally, profits and costs.

Christine

In my research for example, I had a case where they had a smart grid with a social housing community. And what they did is they had solar panels through a rental system. They rented solar panels from the municipal energy supplier. And then in addition to that, they installed a community battery. The batteries sit in a large container at the street corner, and the entire community has access to it. The battery was funded by the distribution system operator and because you need less additional technology than comparable home batteries, it is in some aspects, the cheaper option, and it means that the tenants didn't have to invest in their own batteries, but they could still get access to the ones that are standing at the corner. I think that was a good and rare example of how these technologies can be made accessible to a social housing community,

Festive opening of a neighbourhood battery near Amsterdam (Photo by Liander).

Marten

You also mentioned empowerment and transparency. Did this project also do anything in that dimension? Did it allow a greater scope for action? Or it is only question about costs and benefits?

Christine

Transparency is really important when you talk data governance or data management. It's very important that for the system is transparent and it is understandable how their personal data is used and by whom. And like we said before, electricity is invisible and you can only see what you can measure. Smart grid systems really rely on sharing and measurements of detailed, real-real time energy data. With just this data you can interpret actually quite in detail what is going on or what people are doing in the household. At the end we're not using electricity for the sake of using electricity but we're using it for cooking, or maybe even for heating, or using it for lighting, or using it for entertainment. And it has privacy implications if you can look at my personal energy consumption, and tell if I'm watching TV, or whether I have a very inefficient fridge.

And so in the system, if we talk about transparency, I would find it really important to define it as such that it is very clear to the user what is happening to that data. This transparency and privacy aspect of justice is something that is discussed a lot already with other digital systems, or with apps. For example, that when we scroll through all the terms and conditions, and we just click on “I accept” because it's really fine print, we don't really read it and we don't really understand it. In smart grids as well then, it’s important that these systems are designed so that doesn't happen. That in an app before I click, I agree, and somebody has really put some effort in to making sure that I can give my consent to the data used in an informed way.

Marten

Have you seen any examples of that being done well?

Christine

To be honest, not yet that much. I also found in my empirical research that this issue was often not seen as an aspect of fairness. I found this startling, because we're talking about this so much with respect to other digital solutions or apps. When we talk about Facebook, when we when we talk about digital platforms like Airbnb, we're talking about it all the time, but not here. I found two reasons for that. One is that smart grids are seen much more as an energy system than as a data-based system. So, this aspect of how much they rely on real-time sharing of data is not discussed. There's not that salience for many users yet.

I think the second reason was that the pilot projects that I looked at in my research, they are often a collaboration of research institutes, of distribution system operators and citizens, and they are very much presented and framed as research projects. And I found that many of the users especially said, ‘well, we don't think this is an aspect of fairness right now, because we're doing the research. And we want to contribute to that research’. But they were also quite clear that if the same app or the same in-home display would be supplied by a regular market party in the future, they would be way more critical. The framing of the project as research played a huge role here. So I would be tempted to say that the more widespread the systems become, the more users see it as data-based systems and the more it is not framed as research anymore, but just a regular service that is also in the market, the more important or salient these data issues will become.

Marten

So DSOs or energy companies should already be thinking about and designing for this right now basically.

Christine

Yeah. Because if not, it could be a barrier to the adoption of those systems in the future. Or at least slow them down.

Christine and I had to wrap it there, but as you could see from the infographic, she has thought these aspects of justice in more domains that he ones we covered here. All in all, these domains of energy justice build up to step by step guideline for designers. Are you a designer and you want to do right by your pilot participants and energy users? Get in touch or sound off in the comments! If you feel Christine’s ideas should be taken up more widely, please share this letter with your community.

This newsletter gets a scoop on Christine’s findings, because the article hasn’t been published yet (I will update this page once it is). If you’d like to read some of Christine’s other work in the meantime, check out the following references.

Milchram, C., Hillerbrand, R., van de Kaa, G., Doorn, N. and Künneke, R., (2018), Energy Justice and Smart Grid Systems: Evidence from the Netherlands and the United Kingdom. Applied Energy, 229, 1244–1259. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2018.08.053 (Open Access)

Milchram, C., van de Kaa, G., Doorn, N. and Künneke, R., (2018), Moral Values as Factors for Social Acceptance of Smart Grid Technologies. Sustainability, 10(8), 2703. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10082703

If you do not have the appropriate credentials to cross the paywall to these articles, maybe you can check out sci-hub.tw (just copy paste the doi number), or if you are uncomfortable with that, send me a message and I’ll lend you a copy.

Milchram, C., Märker, C., Schlör, H., Künneke, R. and Kaa, G. Van De, (2019), Understanding the role of values in institutional change: the case of the energy transition. Energy, Sustainability and Society, 9(46). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13705-019-0235-y (Open Access)

Bonus photo by Olivier Middendorp that does justice (get it?) to the dramatic potential of smart grids (via NRC).