(R)evolutionary change

On the influence of evolutionary science on transition scholarship

Hi all. This week I’m starting something new. This semester, I have returned to my doctoral alma mater to teach some undergrad anthropology classes. One is a history and theory of anthropology class. Why, you ask, does this bear on this newsletter? Well, because the history and theory of anthropology is a lot of fun and you can make it bear on anything! More specifically though, I think it’s worth finding out if it can be a revealing window onto (the science of) sustainable energy transitions. So in the next few weeks, I’ll start each edition with a very quick introduction into a particular moment in the history of the science to end all social science. From there I’ll make excursions into whatever thematic landscape that opens up. Let me know if it works for you, or if it’s not what you signed up for, literally.

Once upon a time, in the second half of the 19th century to be (a little) more precise, Darwin had made his mark on the spirit of the time – evolution was everywhere, including in the burgeoning ‘life sciences’. Herbert Spencer had introduced Social Darwinism, Auguste Comte’s philosophy of science revolved around a theory of the evolution of the human mind, and the social science All-Father Durkheim toyed with not-quite evolutionist theories of societal complexification.

The beginnings of anthropology were no different: the global variety of human cultural expression was explained through a limited number of developmental stages of human culture. Thus, Lewis Henry Morgan drew up the – self-admittedly speculative – schematics for a three-step rocket of human culture, igniting in savagery, cruising through barbarism and landing in civilisation, each stage enabled by key technological advances. Edward Burnett Tylor mused that while ‘culture’ was shared universally, some people seemed to have, er, more of it, raising them to levels of true civilization.

A key proposition they shared was the unilinear development of culture – culture starts out in a primitive state and then finds it ultimate destination in western civilization. (It seems they didn’t read science-fiction.) It wasn’t very sophisticated theorizing. (In fact, it was a crutch - whenever they put aside their evolutionist ambitions, they did much more interesting work.)

Pour la pétite histoire, I want to give a special shout out here to Anténor Firmin, who was the ambassador of independent Haiti to France and the author of an 1885 book on “the equality of the races” – a proposal for a non-racist evolutionist anthropology.

Delectably, Firmin collects all his predecessors’ various attempts to delineate and enumerate the human races, communicating quite effectively how ridiculously doomed their effort was. (Though I’m not sure his contemporaries were able take that step back – perhaps they still saw meaningful argument where we now see futile sophistry. Hopefully, in another 150 years, someone will laugh at our fruitless scholarly squabbles. Speaking of squabbles, time to dig in!)

It took a couple of decades, but by the 1920s, the idea that cultures were like species and had, consequently, ‘evolved’ in the same way had been banished to the margins of the discipline. However, the idea of cultural or societal advancement – as well as the notions of superiority to which it was inextricably tied – refused to quite die and its zombie descendants have led quite comfortable lives among us. One example is modernization theory, one version of which started out with an actual rocket-inspired theory of societal development. I won’t talk about that today though. One of its later spin-offs is ecological modernization, a quite influential school of thought in environmental policy, which I think merits its own newsletter. TBC!

Instead I’ll dedicate the remainder of this first comparison to another characteristic of evolutionism: its emulation of the natural sciences. For these have also served as fount of inspiration for sustainable transition scholars.

Capturing complex social change

The OG evolutionary theory has, of course, flourished since then. However, this is no longer your common 19th century garden variety of Darwinism (only the fittest survive!). Evolution science has evolved. (Sorry.) And that means it offers new conceptual models to try out.

The reason for trying them out has also changed. One of most influential schools of transition studies – the ‘multi-level approach’ – turned to evolutionary theory in its need to find concepts that could deal with complexity better than existing approaches. (Smith et al 2010: 437) For example, at the time, environmental economics (and some policy wonks still today) only considered pricing mechanisms as tools to redirect economic growth into sustainable pathways. By pricing environmental externalities (say, through a carbon tax), you make environmental stewardship relatively cheaper. Fine, but if only it were so easy. It is not. (If it were, then threats by companies to move out of your country if you institute carbon taxes wouldn’t actually be hollow!)

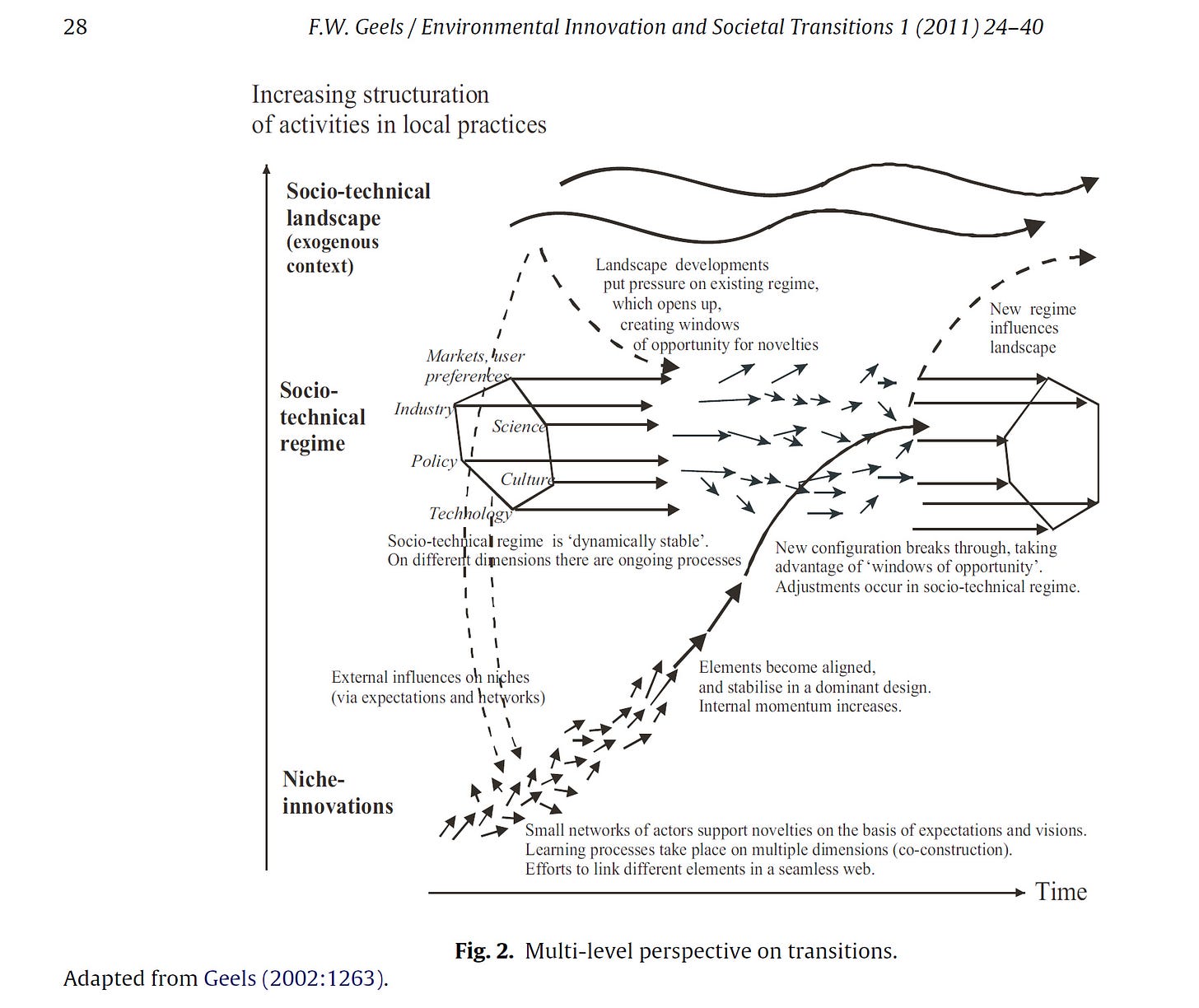

This is a major difference with the good ol’ evolutionism: the latter’s retrospective perspective explained all the complexity of human existence away by placing everyone on the One Great Line of cultural evolution. Contemporary “quasi-evolutionary” (Smith et al 2010: 439) approaches, by contrast, are actually trying to invite in more complexity. The well-known triad of landscape, regime and niches – each with its own (interacting) logics – comes from that.

Complexity. From here.

Let me give one example of a new concept that policy scientists have adopted: the ‘punctuated equilibrium’. The idea comes from ecology, where scientists have argued that habitats or ecological ‘systems’ tend towards stabilization – i.e., that its different species kind of hold each other in a self-perpetuating balance.

In the human social world, we erect institutions to do this stabilizing work, and when different groups in society are locked into certain (power) relations, things may look like they’re stable. But in fact, they are not. Things are constantly changing, even the institutions that were meant to keep things as they were. So what’s the use then of a concept like equilibrium? Specifically, what is its use for transition studies? Isn’t the very object of transition scholarship change itself?

Well, in a sense the very object of sustainable transition scholarship is actually delayed change – frustrating, long-in-the-works, delayed change. Its real objective is to understand why change is either not heading in the desired direction, or not heading there faster.

Evolutionary theory and the GND

A notion like ‘punctuated equilibrium’ helps frame this slow process (see for example Boushey 2012). With it, we can understand the instability in our stabilizing institutions and in our interlocking social relations as a slow undermining process that, once it reaches a certain level or point, pierces the equilibrium and inaugurates a systemic shift – in what Joseph Huber in 1982 called the switchover point (listen here for this theory’s OST). At a general level, the frame helps find reasons for hope where otherwise none would be found. However, I don’t know if it helps to actually understand when breakthroughs are made, or how to make them.

To me more specific, I wonder if a quick transition like the one proposed in the Green New Deals has use for this type of evolutionary theory. (See this recent issue on how transition science has started wrestling with this same question.) The Green New Deal proposes a revolution, if you’ll allow the wordplay. It’s about fundamental and rapid changes to the political economy of a country and its greenhouse gas emissions. These fundamental changes occur primarily in the landscape and regime level (less so in niches – innovations are difficult to legislate, though easy to promote). Trying to figure how all these levels are going to ‘co-evolve’, then, becomes, to put it strongly, obsolete.

I usually don’t put things very strongly, so this is not me announcing that all multi-level scholarship is going out the window and from now on we are only going to read Marxists here. Even if I’m right and multi-level approaches are not the most useful for fast and furious transitions, well, the world is too darn complex for just one theory to capture.

Aight, I kinda shot from the hip today – I probably didn’t hit the mark every time, but I hopefully enough to perhaps set some new trains of thought in motion. Others in this series will be less meta, more concrete.

Sources

Boushey, Graeme. 2012. "Punctuated Equilibrium Theory and the Diffusion of Innovations". Policy Studies Journal. 40 (1): 127-146. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/j.1541-0072.2011.00437.x

Smith A., Voss J.-P., and Grin J. 2010. "Innovation studies and sustainability transitions: The allure of the multi-level perspective and its challenges". Research Policy. 39 (4): 435-448. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2010.01.023

If you do not have the appropriate credentials to cross the paywall to these articles, maybe you can check out https://sci-hub.tw (just copy paste in the doi number), or if you are uncomfortable with that, send me a message and I’ll lend you a copy.