Policy solutions to curb elite overconsumption

Conventional, reformist and radical strategies to reduce energy and emissions footprint fast

Dear people,

apologies for staying away for a month. I had to take some time off to be with family, but here I am again, so let’s dive into it.

We’re trying to figure out if we can make a dent in our global carbon footprint by some surgical interventions targeting the Big Spenders among us. My conclusion so far: in essence no, because Big Spenders are, in the end, just as part of the system as everybody else. That doesn’t mean we shouldn’t do try and curb elite consumption, it just means there aren’t (m)any quick fixes.

But let’s take it from the top.

Is elite consumption different?

If you want to target elite consumption, you have to know what to target. Can we single it out from other forms of consumption? Well, sorta kinda. Let’s say that we can come a good way. First, one could take a quantitative approach. Let’s take a look at the numbers from last issue again.

Seen from this perspective, elite consumption is anything that stands in the way of getting everyone to that shared personal emissions goal. Practically speaking, you’d probably wind up starting with the things that only (very) rich people do or have, because as we’ve seen, these tend to have the biggest energy requirements and emissions impact per use or per item.

But perhaps this purely-by-the-numbers is an unsatisfying approach. It might lead to unfortunate priorities, with policies coming down on practices or technologies that are essential in some way.

So, another, supplementary way of looking at the reduction of the impact of consumption is the decent living or human well-being standard (discussed, among others in this article by Thomas Wiedmann and others).

We want everybody to have a decent life, free from ‘want’ of necessities. Now, what is necessary and what is not, is very clear at the extremes and gets very muddy towards the middle, and (necessarily political) answers will vary per context. Still, the decent life standard allows us to formulate a principle, which says that superfluous consumption is “consumption that does not contribute to needs satisfaction”. At lot of this superfluous consumption takes place at the “super-affluent” end of the scale.

So, if we can identify and isolate such superfluous consumption to some extent, the next question is: can we target it also with policies?

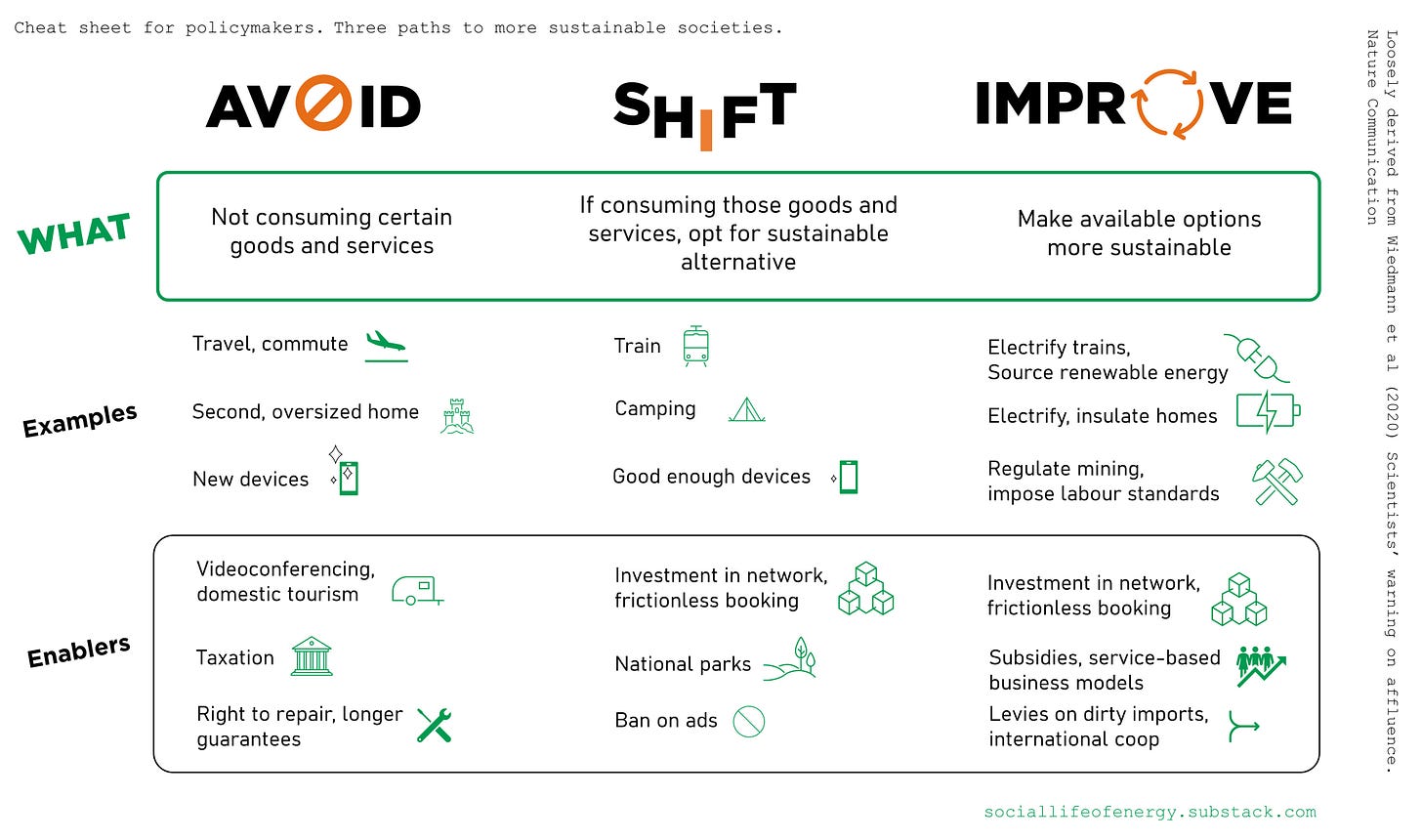

Avoid🚫-Shift👯♂️-Improve👌

To answer that question, let’s first again clarify what this would mean in policy terms. For that, I call on the Avoid-Shift-Improve Framework. This framework comes from the study of sustainable transport in Germany, but it’s helpful to think about consumption in general.

Avoid: not consuming certain goods and services, or less of it. Like not going from A to B.

Shift: when you need to consume a type of good or service (like going from A to B), you take the more sustainable version (means of transport, in this case).

Improve: making sure that a particular good or service (whatever mode of transport people choose) is the most efficient, greenest it can be.

Three policy flavours

This is not going to be easy. Take a look again at that graph from last week: the reduction in emissions/consumption is enormous for the elite. There is a lot of economic activity - and therefore a lot of livelihoods - involved in providing the goods and services that produce these emissions inequities. One could easily imagine significant economic consequences if that drop would actually occur within 8 years. It doesn’t actually take too much to send off a cascade of ever deeper disruptions.

At the same time, it is also increasingly clear that our current policy framework falls woefully short of preventing the worst climate change. People are therefore thinking about what it would take to still make those drastic changes in a socially and economically sustainable way.

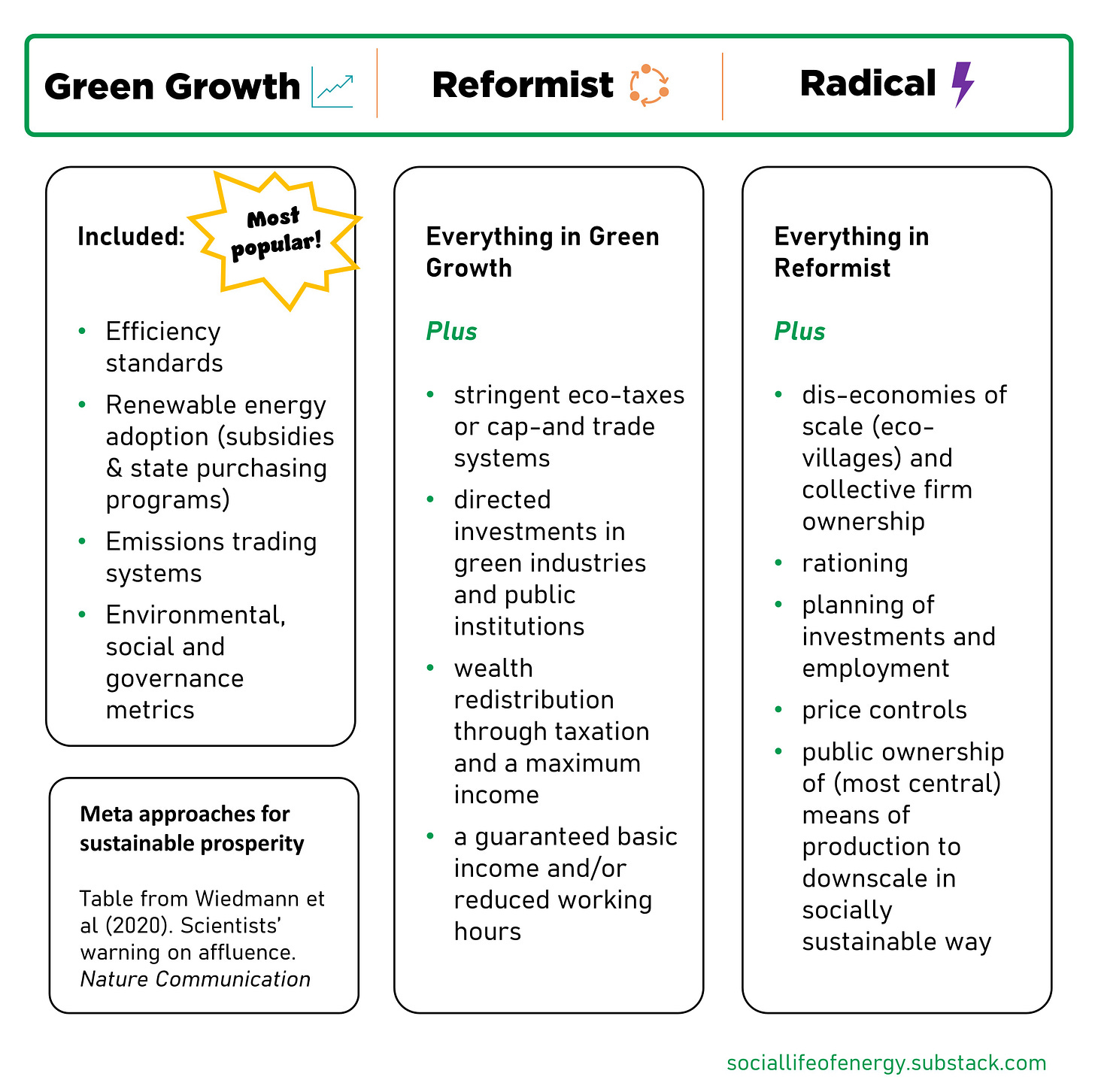

Based on an initial policy survey by Samuel Alexander and Jonathan Rutherford, Weidmann and colleagues distinguish between three philosophical flavours in how to approach this: the status quo a.k.a. eco-modernism, reformism or radicalism.

Three policy examples

Can we think of ways to target superfluous consumption, bring down that disparity to something more equal and thus reduce energy needs and emissions? Are these ways politically and economically feasible? Let’s review some concrete proposals:

Choice editing (a radical avoid strategy): the “simplest” way to make sure something doesn’t happen is to prohibit it. When you ban something, people can’t choose to do it anymore (except if you can’t enforce the ban, of course). Hence the name. An example where this could work: aviation. Banning domestic flights like they did in France. However, while that targets a relatively elite means of consumption, it’s still fairly indiscriminate and might hurt people who depend on it. So it only works if there are viable and affordable alternatives.

In short: this particular example is effective in reducing emissions, not so good in singling out elite consumption.Tax and dividend (a reformist avoid strategy): you tax a noxious practice, increasing its price, and you give the resulting money to people who need it. It’s a nice idea, but there are questions about whether it will politically work. It also doesn’t stop the activity in and of itself (unless it’s super heavily taxed, which is not likely), because the people who can afford the product, can probably also afford the taxes. For example, let’s stay in aviation: a frequent flyer levy, which progressively taxes air travel.

In short: good at targeting elite consumption, not so good at reducing emissions.Personal Carbon Budget (a radical avoid-shift-and-improve strategy - ideally): now for a more comprehensive and thus more radical idea. Each citizen gets to emit some carbon ‘for free’, but anything above that will cost them. You can immediately spot the difficulties: it individualizes responsibility, will hurt those who don’t have the $$$ budget to buy themselves indulgences or reduce their footprint. So, for this to make sense, it could only be as complement to systemic change that makes low-carbon options widely available; make it progressive, reducing the budget year over year and make the price of extra carbon credits dependent on income.

In short: could be good in reducing emissions, could be good at targeting elite consumption, but it all depends on execution. (Speaking of which: these three options are administratively increasingly complex, not to say convoluted.)

None of these policies are likely to happen in the current moment. But intuitively I would say there is a greater chance that “climate” is taken as legitimate ground for these “unfair” policies that target privilege than arguments for social well-being, especially when it is clear that doing so will avoid more emissions more rapidly. It’s just a hunch though: do you know of (attitudinal or historical) research that would back this up or debunk it?

The necessity and ‘impossibility’ of reducing consumption

The point behind the more decisive policy interventions discussed by Weidmann and colleagues is that there is no reason to assume we can green production to the point where consumption no longer leads to climate change. Certainly not in the short run, which is the run that matters most in terms of preventing irreversible climate change. And so we need to strategically reduce consumption.

But curbing consumption (through progressive taxation, banning certain ads) is radical, at least for most of the Global North. A confluence of a belief in individual responsibility, the freedom of the market, and the fact that the noxious effects of this resource-intensive consumption has not sunken in sufficiently for key decision-makers keeps this idea outside of the Overton window for now. That the most powerful solutions involve wealth redistribution of course doesn’t help.

However, with shocks, opinions can suddenly pivot, as we’ve seen dramatically with Covid-19, or the war in Ukraine. It is therefore important to keep working on and sharing these ideas, so that they are ready when their time has come. (In that sense, the fact that the UN now explicitly recognizes inequality as a contributing factor to climate change is perhaps a sign of that time.)

On this hopeful note, I salute thee and wish thee well. Let me know if you have some tips for future issues on these topics!

Best,

Marten