Leveling the playing field for energy communities

Redistributing risks of sustainable electricity grids

Hello, and welcome back to the Social Life of Energy!

Last issue I placed the problems that occurred with the Texas Freeze in a larger regulatory picture. The ridiculous response of certain conservatives was to blame the blackouts on particular methods of energy generation. In fact, regulation was the problem – allowing the system to freeze to a standstill as well as inflicting uneven sorrow on different people. Unfortunately, I kindly reminded you, these regulatory shortcomings would keep plaguing energy provisioning and keep creating inequalities even as the grid continued to switch to renewables.

Ah, but Marten, you may have said, surely if we outfitted towns with solar panels, added batteries for some buffer capacity and created microgrids, these communities would become more self-sufficient and resilient!

Well, I would reply (I mean, if you were to have said that), that surely sounds like a good idea and I wouldn’t want to imply that choice of technology makes no difference. However: outfitting towns with VP, batteries and microgrids is actually super complex and requires… regulation.

Today, I want to give a you a glimpse of that complexity. I’ll review the attempts in the European Union to empower communities, allowing citizens to take the improvement of their energy provisioning partly into their own hands and take part in the great transition towards a green grid.

My main message will go something like this:

even if you have a well-intentioned regulator (not a given), because of the speed of developments, the complexity of the digitalized renewable grid, and because of competing interests, it’s very easy to get this transformation wrong and wind up with the opposite of what had you intended.

Today’s newsletter is informed by my collaboration with a wonderful group of people in the Horizon2020 funded NRG2peers project, where we try and figure out how to, er, empower energy communities to participate in flexibility markets.

Mostly I’ll stick to reviewing two excellent, comprehensive texts though, which I am now going to simplify into a bunch of bullet points.

Roberts, Joshua. 2020. "Power to the people? Implications of the Clean Energy Package for the role of community ownership in Europe's energy transition". Review of European, Comparative & International Environmental Law. 29 (2): 232-244.

Savaresi, Annalisa. 2019. "The Rise of Community Energy from Grassroots to Mainstream: The Role of Law and Policy". Journal of Environmental Law. 31 (3): 487-510.

Buckle up, and see you on the other side.

So, many people pining for reliable, affordable and clean energy have pinned their hope on community ownership. That is: in theory, as energy production is decentralizing, it should become easier for smaller groups of citizens to ‘buy into’ the grid of the future and reap its benefits themselves – instead of being dependent on the big boyz.

The evidence for this theory is uneven: in some countries, communities did and do own quite a bit of small-scale energy generation capacity, but we’ve also seen the big boyz take over this scene.

Also, in the earlier phase of decentralization, the business case for small scale renewable generation was relatively easy to make. All it needed was dwindling costs plus straightforward incentives like the feed-in-tariff guaranteeing fairly quick returns on investment.

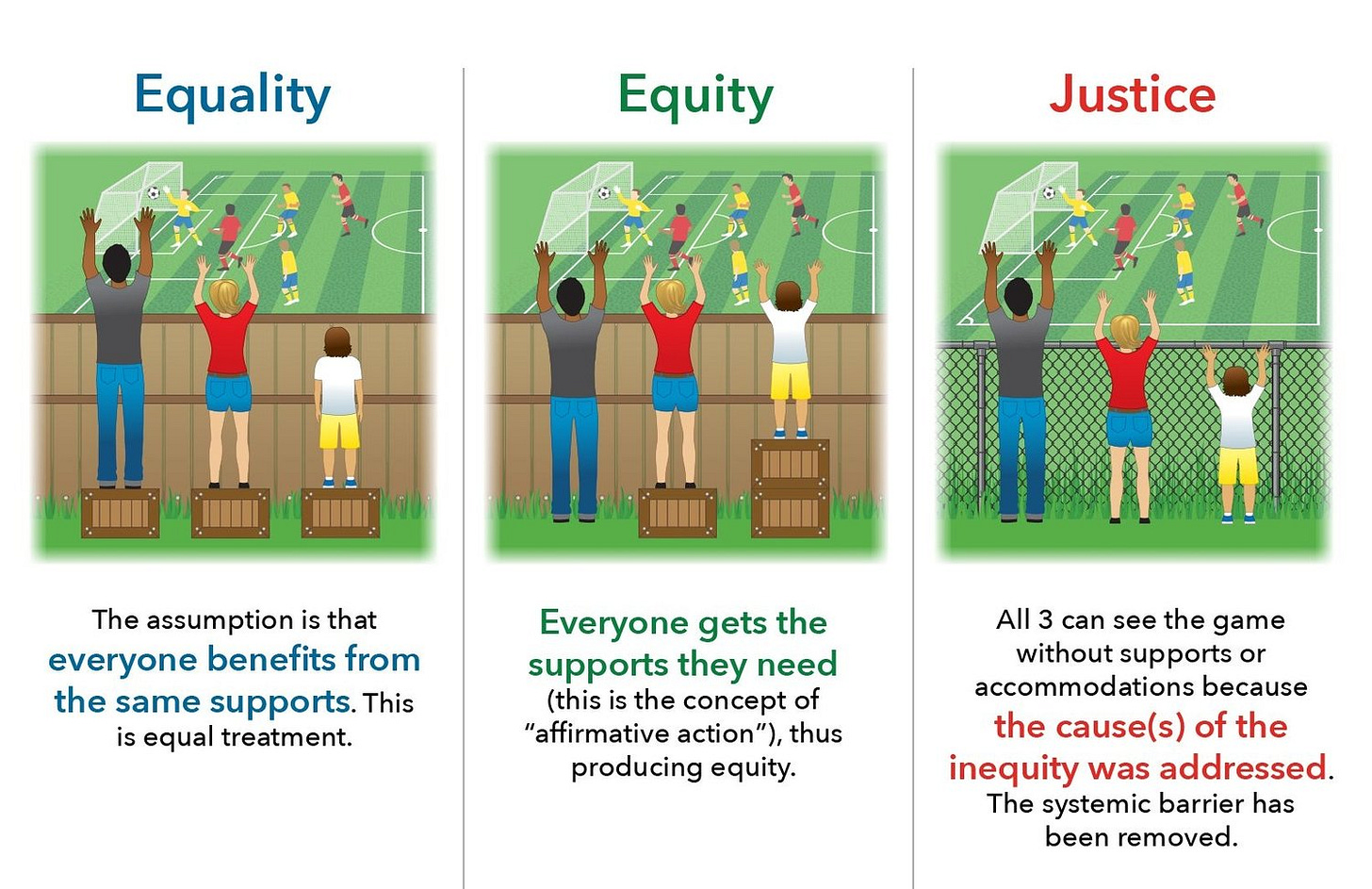

A little interlude here about markets: these simple support policies died an inglorious death in the European free market – with devastating effects on community energy participation in frontrunner countries (see Roberts, p. 3; Savaresi, p. 502). Now, liberalization of the energy markets has made community energy possible. Decentralized energy generation or not, if nobody was allowed to hook up anything, the decentralized grid wouldn’t be any more plural than the old one. But in the obsession (?) to create a “neutral” marketplace, the EU regulators banned ‘discriminatory’ policies like differential Feed-in-Tariffs. But power often parades as neutrality. And so it happened that the free market wound up working better for the big boyz. With time though, and some gentle pressure from the cooperative new kids on the block [Error: soundtrack not available], EU policy-makers realized the true and deep meaning of equality:

So, in two updates of its energy directives, it came around to a (sort of) positive discrimination approach, exhorting member countries to do their best to assist energy communities.

The recast Renewables Directive requires Member States to adopt ‘enabling frameworks to promote and facilitate’ both renewable energy communities and renewable self-consumption, by removing unjustified regulatory and administrative barriers. (Savaresi: 493)

Problem: the current phase of decentralization is more complicated: quite heavy investments with longer rates of return; highly complex markets; and a digital layer that requires specialized expertise to devise and operate.

Specialized expertise means relying on third parties, which is not bad per se, but this new dependence does also open the door to co-optation of the energy community by larger players.

In sum: the regulatory intention is now good. But, as Roberts points out, this is just the beginning. What the EU did was formulate the legislative principles. Now comes to hard part, aka the transposition process. That’s when member states adopt EU directives into national law.

The difficult part: lack of familiarity with ‘energy communities’, potential resistance from incumbent big boyz, and the complexity of the market.

In terms of the first two difficulties, based on our assessments in NRG2peers we can be moderately optimistic.

We reviewed the situation in four countries: Italy and Spain are staying very close to the directives, actually with some additional provisions for combating energy poverty. The Netherlands is trying to be a little creative, but in the spirit of the directives. Slovenia is perhaps an example of a country that was utterly unfamiliar with community energy, but seems to be catching up quickly with successive and corrective legislative efforts. So, in terms of the politics of the law, it seems that the community energy is doing fairly well.

That still leaves the complexity of the market. Because even if the principles are safely transposed, it still gets hairy in the details.

“The evidence from pioneering States suggests that there are regulatory complexities associated with the mainstreaming of community energy, which are not easy to resolve”. (Savaresi: 489)

Let’s take two examples (from Savaresi). First: capacity-building. The EU requires member states to provide support and because of all that market complexity, it’s sorely needed. But the kind of support a country can provide depends on its existing regulatory system. Thus, in Denmark and Germany, energy communities were bolstered because of “extensive powers of local authorities in planning and public services”. In the UK, no such local powers existed, so instead authorities helped grow a new field of intermediaries. For the most part, their ties with communities are symbiotic, but at the same time, this system creates new dependencies and thus the need for more regulation to protect the dependent parties from potential abuse.

The second example is access to the grid, to which communities have a right, so long as they pay their fair share for it. What is a fair share though? In the UK, high connection costs have kept communities from linking in. There’s also the matter of locality, discussed in this SLE issue: energy communities usually want to serve their locality, but in the Netherlands, they can’t do so exclusively – once hooked up, they must serve connections across the whole grid, thus complicating matters.

So, there we are. This is but a teensy tiny selection of the issues. Moral of the story: building a clean grid with ‘citizens at its core’ will be a fight in the worst of cases and a long road of two steps forward, one step back in the best of cases.

The “energy communities” that are the focus of EU legislation are not the only kind of “community energy”. One other form is partial ownership of new generation capacity, like wind farms. Next issue, I’d like to end this triptych on wind with a review of what we know about the effect of the degree of involvement and financial benefit on “acceptance”.

In the meantime, I wouldn’t be surprised if I had gotten something wrong here. If I did, let me know!

And in the mean meantime, though we’re far from Texas, and corridos (like last week’s about José Mosqueda) aren’t mariachi, let’s say we want to weave some sonic tissue through this series and in so doing give some giddy-up to your weekend.

Best wishes,

Marten

Very good observations concerning a very complex issue. Setting up the "ideal" regulatory framework from scratch would already be very difficult, but in the real world, we need to start from a patchwork of existing regulations and evolve them into something that gives the desired regulatory signals in a fair way. Just looking at recent experiences in Flanders with support for solar panels illustrates how well-intentioned policies can easily lead to significant unintended consequences, with corrective actions then unfairly affecting some citizens that invested in the best available clean home energy technologies.