How to make sure locals benefit from new energy infrastructure

Two steps: decide who the locals are and then reach out them. Easy!

Hello folks, and welcome back to The Social Life of Energy.

Not a subscriber yet? Rectify the situation with the button below

As you may remember, last issue Thijs de Jong (from the cooperative Amsterdam Energie) and I were talking about how to build new sustainable energy infrastructure: by getting (residential) stakeholders involved early on and making sure they stand to reap some (monetary) benefits. There are various ways of doing this: people can buy shares (as under the Danish Co-ownership scheme), whether or not through some kind of cooperative structure (as Thijs and I discussed), locals can get lower energy tariffs, or you can set up a community fund that can invest in local projects.

Why are these mechanisms important?

Well, if you want far-reaching sustainability transitions to succeed, you need to make sure it empowers people and makes their lives better. If you don’t, you’re going to meet either resistance or a lack of capacity. (There are other (ethical) reasons to make sure it does too, but I’ll talk about that in a later issue.) What’s more, in this particular case, the question of how to organize and finance new energy infrastructure is going to come up again and again, because we’ll need to be repurposing a whole lot of land to replace those coal and gas-fired power plants that we have get rid of pronto.

Today, I won’t be evaluating which of the methods of compensation or benefit-sharing is the best. In principle, each method has value. Instead, I’d like to take one step back to address a matter that all these methods will have to face: who is actually going to get these benefits? It’s one thing to say ‘let’s give back to the community’. It’s another thing to decide who your community actually is. Today’s newsletter is about that other thing.

Let’s break the question down into two parts. The first is: what or where is ‘the community’ that will be getting some love. Who are the ‘locals’? If you manage to answer that question, then the second one immediately thrusts itself upon you: will we allow individuals in the community to apply and qualify for benefits or will we distribute them through a collective mechanism?

Let’s turn to an Irish extension of a semi-high voltage transmission line to see how these questions were answered and how the decisions played out.

Devine-Wright and Sherry-Brennan (2019) had a look at a community fund that was set up for a region affected by the new line. The grid company had decided to set up the fund in accordance with the regulator’s general advice to offer compensation (15,000 euros per kilometre for 110 kV lines; 30,000 euros for 220 kV; 40,000 euros for 400 kV). It first had to answer question no 1: who is actually impacted by our transmission towers? Where do we draw the line for who is able to apply to our fund?

110 kV tower pylon in an Irish landscape (image provided by EirGrid and taken from Devine-Wright & Sherry-Brennan (2019).

The authors’ telling of the tale that followed focuses on the wisdom of “pragmatism”, that is, the ability to use multiple criteria for setting rules and then being able to tug and pull at these rules a little when applying them.

They tell the tale in Three Acts: setting up the catchment area; presenting the boundary to the community; and working with the boundary while actually granting projects.

Act I: The grid company started out with the following idea: to draw a rational and universal – and thus fair – line around the transmission line at 2km’s distance. In the end, the foundation included two towns within the catchment area that would have been cut in two by the 2km line – recognizing that the rational limit would have appeared arbitrary rather than universal – but it did not approve smaller towns further away, seen by locals as the hinterland of the two larger towns. One qualitative divergence is not like the other (that’s kinda the nature of the beast).

Mullingar: the town that was allowed to stay together.

Act II: In legitimizing the boundaries to the locals, the fund emphasized the notion of impact (rather than sharing benefits). By and large, later applicants to the fund thought this was a fair enough criterion and the fund itself as a fair enough mechanism to “give back to the community”. Please note that the researchers don’t show the reactions of those falling outside of the ‘impacted community’ who may have felt differently about it.

Act III: Despite having thoroughly thought through the criteria, the panel ran into two main problems once they started judging applications. One, in practice the boundary turned out to be fuzzier than in theory. People living in the area proposed projects outside of the area, and vice versa. There was disagreement about whether such proposals were eligible. Second, the people they felt were particularly deserving of compensation didn’t wind up submitting applications. Most applications instead came from the strongest sections of the region. That gave the board the sense that they had failed to some degree in their mission.

Devine-Wright and Sherry-Brennan do a neat job of writing up the moral of this story.

In a nutshell, they advocate some institutionalization of the flexibility or ‘pragmatism’ that the fund already showed to some degree. For instance, the problem that the most empowered members of the community were the ones to come forward with project proposals (a familiar result of relying on individual initiative to give shape to your ‘community’) could be addressed by employing multiple criteria (at different times).

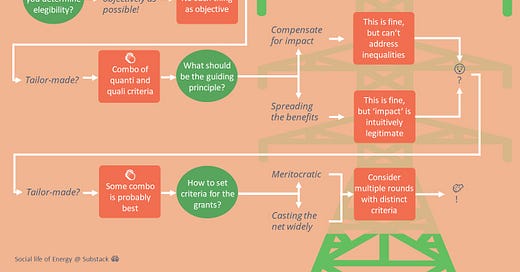

With lessons such as this, they hope to improve the dearth in (more detailed) “policy guidance for developers on how to draw the line” (173). In that spirt, and because I know policymakers are used to reading PowerPoint slides and they like infographics (this is a well-known fact), I summed up the decision-tree Devine-Wright and Sherry-Brennan propose (more or less) by making an infographic in PowerPoint.

You will have undoubtedly noted the central important of tailor-making in designing the fund: there is no way around it. It’s the main lesson Thijs drew from the work his cooperative did with homeowners’ associations and housing corporations, too, and it was Schick and Gad (2015) recommendation after their study on perceptions of consumers among Danish utilities. Not to blow my own profession’s horn here, but every utility should employ a social scientist or two (they get lonely if they don’t have a peer to talk to). You’ll need ‘em for your tailoring.

That is the lesson that I will leave you with today. However, if you didn’t get enough of this topic yet, see below for further reading. For now, I wish you happy and loud horn blowing this coming week.

All the best,

Marten

Source

Devine-Wright P., and Sherry-Brennan F. 2019. "Where do you draw the line? Legitimacy and fairness in constructing community benefit fund boundaries for energy infrastructure projects". Energy Research and Social Science. 54: 166-175. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2019.04.002

Further reading

Clausen, Laura Tolnov, and David Rudolph. 2020. "Renewable energy for sustainable rural development: Synergies and mismatches". Energy Policy. 138. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2020.111289 (Open Access)

A lot of the development of new renewable infrastructure will happen in less densely popular, i.e. rural, areas. These rural areas are often economically depressed. If structured properly – if locals get to share in the benefits – these developments can be valuable investments in rural economies. Unfortunately, as the authors point out, we’re not structuring these developments properly. (In fact, they can seem more like exploitation of otherwise ‘valueless’ land.) Read this article to know what we should pay attention to.

Leer Jørgensen, Marie, Helle Tegner Anker, and Jesper Lassen. 2020. "Distributive fairness and local acceptance of wind turbines: The role of compensation schemes". Energy Policy. 138. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2020.111294

While Devine-Wright and Sherry-Brennan present a fairly hopeful picture that genuine steps towards local communities can see a project and the community through all the imperfections of any benefit-sharing scheme, they recognize that things may be more complicated for more controversial development projects. Jorgensen et al highlight what can go wrong with a few case-studies of wind park compensation schemes in Denmark.

Geschiere, P. (2011). The 1994 forest law in Cameroon: neoliberals betting on "the" community. In N. Schareika,E. Spies, & P-Y. Le Meur (Eds.), Auf dem Boden der Tatsachen: Festschrift für Thomas Bierschenk (pp. 477-494). (Mainzer Beiträge zur Afrika-Forschung; No. 28). Köln: Köppe. https://pure.uva.nl/ws/files/1365514/113046_359318.pdf

Devine-Wright and Sherry-Brennan’s questions about the boundaries of the community remind me of Peter Geschiere’s (mentioned earlier as well) studies of the ever-elusive community: who belongs to us? He wrote the book about it and one chapter deals with how a new sustainable forestry management law promoted by the World Bank, which to reward the local stakeholders for forest protection, aggravated local tension and set in motion a process in which village members attempted to close off a community of core citizens from second-class satellite citizens. This article tells that same story.

PS: If you do not have the appropriate credentials to cross the paywall to these articles, maybe you can check out https://sci-hub.tw (just copy paste in the doi number), or if you are uncomfortable with that, send me a message and I’ll lend you a copy.