Energy of, by and for the people

Keeping the electrons bouncing in local (micro) grids through self-governance

What happens when people want to, or basically have no choice but to, take (greater) responsibility for their own energy provisioning? What rules and resources do people have to keep the energy flowing for all?

Welcome to the third edition on the energy commons — after issues on resistance to the privatization of land on which wind turbines are built and attempts to take energy providers (and grid operators) out of the private market through municipalization, today we're looking into energy communities.

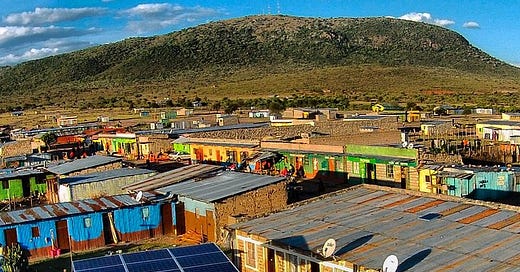

Specifically, we're looking into stories of developing very local energy mini-systems or sub-systems, whether by communities themselves, or by (usually commercial) parties in the service of communities. Such energy solutions are examples of when energy infrastructure and electrons are not really public, not really private, but something else: communal. When the management of energy lies, to greater and lesser degrees, in the hands of the 'commoners'.

When citizen collectives want to take over, they run into a few challenges.

Firstly, though especially in the Global North, they run into the legal and institutional limits of established energy systems. You know this; most of you encounter this inertia of energy provisioning one way or another in your work. It's not what I want to focus on today.

The second challenge is what I want to write about here. This is the challenge of cooperation and coordination. Of self-governance, in other words: setting the rules and abiding by them.

Microgrids are the best examples of this. By design, microgrids need local management in one form or another. In theory, one could try to fully automate the necessary balancing act of supply and demand through 'smart' energy buffers that can absorb and/or dispense energy when needed. In poor settings, this is not even in the realm of fantasy. In rich contexts, it's still mostly fantasy (but dreams at least can come true 🎶). So, microgrids need active contributions from its users on a daily basis. Those contributions require some ‘social’ infrastructure (what non-fancy people call “institutions”).

Building that infrastructures comes with some challenges. I'll present two examples. One set of examples comes from rural settings in Kenya, which could stand in for many other rural places in the Global South where the electricity grid hasn't made much inroads, if at all. The second example comes from a demand response trial in the UK, an example of decentralized renewable electricity generation making "distributed" governance — i.e., local self-management — within extensive grids possible.

Curbing overconsumption in rural microgrids

Running a microgrid is not easy. In a project in India (analyzed here), 9 out of 10 microgrids basically failed. Lorenz Gollwitzer and his colleagues, whose work from 2018 I'll be following over the next few paragraphs, cite a 50-100% failure rate for microgrids (which they call minigrids). There is more than one reason for this, but one recurring factor is the:

collective over-consumption of electricity, which in turn leads to equipment degradation and failure (p152)

The authors explain quite well what the problem of overconsumption consists of precisely (in a quote I lightly edited for brevity and clarity):

There is a limited generation capacity that must be balanced with demand. Both generation capacity and demand typically vary over the day and over seasons, leading to periods of both scarcity and underuse. There can be problems with illegal connections, and some users may under certain circumstances use more than their agreed share. If one electricity user continues to add powerful loads she will eventually overload the system resulting in voltage drops and potentially causing a black out. In other words: actions by one person may lead to reduced performance and potentially damage to the system affecting all users. Finally, because energy can only be stored at very high cost, generation and consumption often need to be more coordinated. (p154)

In addition, most rural minigrids have to rely on flat fees that are easier to administer but which are not cost-reflective and which don't put up any financial barriers for anyone tempted to consume electricity at will.

Before diving into the details of how a few specific Kenyan microgrids tried to deal with this challenge, please note that this challenge looks a lot like what scholars have called 'managing a common pool resource'. The term “Common Pool Resource” is mostly associated with the work of and around Elinor Ostrom, who went on a global quest to find inspiration in communities that are successfully using a common resource sustainably. Water is such a quintessential scarce but replenishable common resource, but, as it turns out, electricity on a local grid is too!

Back to Kenya's minigrids, and back to the solutions community leaders tried to put in place:

What about the good ol'

financial incentive?

It turns out that trying to get energy tariffs to do most of the coordinating legwork is difficult to organize. They tried to do this in one minigrid, and in good democratic fashion, tariffs were set by the community. But this is a small community, and people didn't want to look like they were poor, and basically set the tariffs higher than what they could afford. Keeping tariff setting within the community is also risky because it invites favouritism - peers putting pressure on their primus enter pares to pretty please lower the prices for them, resulting in inequity and financial insolvency.

So, relying on financial incentives invites its own set of challenges. Maybe we can still

offload coordination to technology?

Enter the prepaid meter. A "game changer", one of their interviewees told them. They eliminate the possibility of favouritism and the need for disciplining and conflict resolution when people abuse the grid. Also, you don't have to go around asking people to pay up cash. It's like smart energy contracts on the blockchain, but without the blockchain! (And without being smart!) 🤯

Still, these meters cost more money to install and they won’t prevent abuse in and of themselves. So, in the quest for technocratic solutions, aren’t we overlooking the power of ‘people as infrastructure’? These are villages and while "elite capture" through favouritism is an endemic risk, the capacity to

adjudicate through personal relations

is endemic too. Practice makes, er, well, at least proficient. People know who has a fridge or a TV and it’s relatively easy to find out (especially if a line disconnects) if someone used more than the allocated two bulbs on at night. A stern word with the elders will bring most people back in line.

So, while markets and technologies may help out, in the end, what electricity as a common pool resources needs are: legitimate “local leadership and clear institutional frameworks and use rules”. In particular, it needs

‘use rules’ that are 1) widely understood and implementable and that, through 2) shared community ownership, can contribute to what is 3) widely perceived a fair allocation of benefits and responsibilities (160)

Too much community?

If some of you are like, "wait a second though... a stern word with the elders?! I'm all for community, but the touchy feely, 'united we stand' stuff, not this social control business!" I can tell you, you are not alone. Enter the research of Emilia Melville and her four colleagues, published in 2017. They asked participants in a demand response pilot how they felt about making sure that people would abide by the “use rules” of demand response.

"Demand response", for any eventual non-energy nerd who happens to have wondered into this newsletter (👋👋), is, as defined by the authors, "the decrease or increase of electricity demand in response to moments of scarcity or abundance" of said electricity, respectively. It helps cables happily humming along.

In this case, the pilot participants would be granted a collective €5000 reward if they would 'flatten' the peaks of consumption that could strain the grid. (It wasn’t actually a microgrid, but reducing peaks is the kind of action necessary to run a microgrid, so I'll allow it!)

So the questions for the participants were: are we going to monitor each other, to make sure everyone's doing their bit? If so, are we going to sanction those who are flaking out? And finally, if someone protests an accusation or a sanction, who's going to be the judge??

The resulting responses are A-grade.

Interviewer: If there was a blackout, would you want to know who did it?

Clara: No, because if it had been us then I would be terrified of being lynched.

Interviewer: And if it tells you the names of people?

Anna: I think that’d be horrible. I’d hate that I wouldn’t want to participate if that was how it was going on, it would be a bit like Hitler Youth or something wouldn’t it.

Sure, it may start out with a stern word, but things can quickly escalate!

In response to other questions about making household's electricity consumption visible, participants talked about voyeurism, embarrassment and shaming that would get in the way of working together towards a goal. So, ‘yes’ to feedback that tells you you're not doing this all by your futile self, but ‘no’ to policing.

Is there no role for the individualist community then? Are prices the only coordinating mechanism at their disposal? The participants leave open the possibility of a layer of coordination on top of a foundation of price incentives: a compassionate encourage-and-reward approach that takes into account people's situation, and thus their capability to 'respond', and lets live the (minority of) people that are 'never going to participate'.

While possible, it wasn't at all clear how they would do that. Deciding on the rules and interventions takes a lot of time and effort 🤔. It's easier (if not necessarily better) to outsource it to a third party, like an energy company, so they mused.

Here, as with the ‘Hitler Youth’ take on mutual monitoring, people appear to overestimate the impact and burden. The authors conclude therefore that while the idea of a ‘united we stand’ community is quite appealing to people, “the idea of community accountability is alien and frightening”.

Citizens themselves, not just the politicians, system operators and Big Renewable, might therefore not be ready for the commons. Still, other instances of community-run grids, both in the Global North and South, show that it can be done, and so Melville and her colleagues advocate experimenting with the “electric commons”, slowly building up experience and familiarity and providing inspiration for a new set of design principles for smart energy communities, that build on Elinor Ostrom's work on common pool resource management.

I rambled on for a long time. Apologies and thanks for making it all way down here! I will have one more thing to say about the commons as one of the Big Swings at sustainable energy that we haven’t figured out yet. It’ll be sort of a wrap up.

I actually might have some inspiration of myself to report from the energy anthropology community that I will meet at the conference of European social anthropologist this week, the theme of which is… Transformation, Hope and the Commons!🙏

Marten

Sources

Gollwitzer Lorenz, David Ockwell, Ben Muok, Adrian Ely & Helene Ahlborg. 2018. "Rethinking the sustainability and institutional governance of electricity access and mini-grids: Electricity as a common pool resource". Energy Research and Social Science. 39: 152-161.

Melville, Emilia, Ian Christie, Kate Burningham, Celia Way, and Phil Hampshire. 2017. "The electric commons: A qualitative study of community accountability". Energy Policy. 106: 12-21.

Wolsink, Maarten. 2020. "Distributed energy systems as common goods: Socio-political acceptance of renewables in intelligent microgrids". Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews. 127.